The King James Bible

Queen Elizabeth was succeeded in 1603 by Prince James VI of Scotland who became King James I of England. The King inherited a church that was deeply divided between the Conformists and the Puritans. To try to settle the differences, the King called a conference in January 1604. The conference failed to produce peace between the contending groups, but it produced a call for a new authorized version of the Bible.

James I

The plea was accepted by King James. Like Elizabeth, he hated the Geneva Bible, but he recognized that the Bishop’s Bible was inferior. He desired to have a high quality English Bible that all his subjects could embrace.

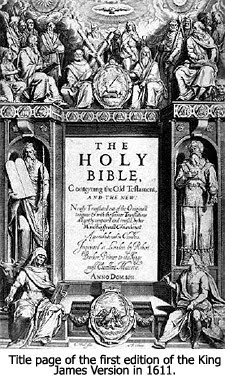

A group of 47 translators were assembled, all from the Church of England. Detailed instructions were issued to guide the translation. Marginal notes were outlawed, except for the explanation of Hebrew or Greek words. The translation had to reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England.18

The translators were authorized to consult other English translations, and they did so. In fact, their work turned out to be more of a revision of existing translations than it was an original translation. They acknowledged this fact in the preface they attached to the Bible:19

Truly (good Christian reader) we never thought from the beginning, that we should need to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one… but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one…

Again, like all the previous English versions, the King James Bible retained 85 percent of the New Testament text of Tyndale. And biblical expert Edgar J. Goodspeed contends that 19/20ths of the King James Version was borrowed from previous translations.20

In obedience to their instructions, the King James translators did not provide any marginal interpretations of the text. They did, however, provide 9,000 cross references and 8,500 notes regarding alternative renderings or variant source texts.

The Ascendancy of the King James Bible

The King James Bible did not become the predominant Bible overnight. Scholars stuck with the Latin Vulgate and abandoned it slowly over the course of the 18th Century. The general public clung to the Geneva Bible for decades.

The turning point for acceptance of the King James Version occurred after the death of King James in 1625. His successor, Charles I, appointed an Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, who immediately banned the printing of the Geneva Bible in order to bring about a uniformity of Bibles. At first, this caused no problem because copies could easily be imported. But Laud later issued a further edict forbidding the Bible’s importation. The last printing of this Great Bible was done in Amsterdam in 1644.21

With no continuing competition, by 1700, the King James Version had become the sole English translation for use in the Protestant Churches.

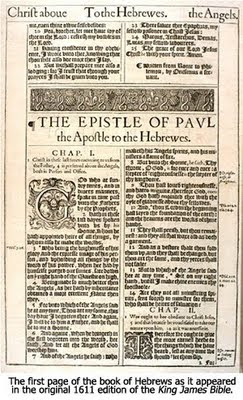

Over the years that followed, the King James Version went through many revisions. Most of these were to correct spelling errors and typographical errors. By the mid-18th Century the misprints had reached scandalous proportions. It was then decided that an attempt should be made to produce a standard text.

The first attempt was by Cambridge University scholars in 1762. Another effort was made in 1769 by Oxford University, and that edition became the standard text that is still in use today.

The Oxford edition of 1769 differs from the 1611 text in 24,000 places. Spelling and punctuation were standardized. The “supplied” words not found in the original languages were greatly revised and extended as a result of cross-checking against the presumed source texts. And in many places minor changes to the text itself were made.22

The Decline of the King James Bible

The King James Bible remained supreme for a peak period of 250 years, from 1700 to 1950. During that time it became the only book in the world to exceed one billion copies.23

The first serious challenge to the King James Version appeared in 1885 when the English Revised Version was published in England. Its stated purpose was “to adapt the King James Version to the present state of the English language… and to the present standards of biblical scholarship.”24

The English Revised Version was noted for being the first Bible to ever be published without the Apocrypha (14 intertestament books). Until that time, all Bibles, both Protestant and Catholic — including the King James Bible — had been published with the Apocrypha.

American scholars followed suit in 1901 with the publication of the American Standard Version. It was nearly identical to the English Revised Version except for the much more frequent use of the term Jehovah in the Old Testament.25

By the mid-20th Century the wording of the King James Version had become antiquated to the point that many words were unintelligible and others actually meant the opposite of their original meaning. This serious problem prompted an explosion of new translations and paraphrases during the second half of the century.

In the fourth and last segment on this series teaching on the Bibles of the Reformation, we’ll look at the modern-day Bibles which began replacing the King James Version.

Notes

18) For a list of all the instructions given by King James to the translators, see, “History of the King James Version,” www.bibleresearcher.com/kjvhist.html, pages 2-3.

19) Edgar J. Goodspeed, “The Translators to the Reader: Preface of the King James Version of 1611,” http://watch.pair.com/thesispreface.html, page 5.

20) Ibid., page 4.

21) Dr. Herbert Samworth, “The King James Bible,” http://www.solagroup.org/articles/historyofthebible/hotb_0015.html, page 3.

22) Wikipedia, “Authorized King James Version,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authorized_King_James_Version, page 20.

23) Jeffcoat, “English Bible History,” page 7.

24) Wikipedia, “Revised Version,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revised_Version, page 1.

25) Ibid., page 2.