The United Nations Solution

In late August the UNSCOP report was released. The Committee agreed unanimously to recommend ending the mandate as soon as possible. The majority (7 to 3, with one abstention) recommended partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. The minority called for a federation with Arab and Jewish cantons.6 The Jews reluctantly accepted the report. The Arabs passionately rejected it and threatened war should the United Nations approve partition.

The UNSCOP proposal proposed an Arab state composed of three areas: the Gaza Strip, the Central Highlands of Judea and Samaria, and the Western Galilee. These areas were intertwined serpent-like with the areas allotted to Israel: the Eastern Galilee, the Coastal Plain, and the Negev Desert. The Arab state would embrace 4,500 square miles, with 840,000 Arabs and 10,000 Jews. The Jewish state would encompass 5,500 square miles, with 538,000 Jews and 397,000 Arabs. Jerusalem and Bethlehem were to be internationalized. These cities contained a combined total of 100,000 Jews and the same number of Arabs.7

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations voted to adopt the UNSCOP recommendations to partition Palestine and create both Jewish and Arab states. The vote in favor totaled 33 and included the United States and Russia. Thirteen voted against, including all eleven Muslim states. There were ten abstentions, including Britain. The resolution required a two-thirds vote of those voting, so it passed with votes to spare. The deciding bloc turned out to be the nations of Latin America. All of them, with the exception of Cuba, voted in favor of the resolution.8

Jews all over the world broke out in rejoicing, but the Jewish leaders knew that the fight was not over. As the Arabs rattled their sabers, the Jews launched a massive public relations campaign aimed at keeping the United States committed to partition.

Headlines of the Palestine Post on May 14, 1948.

The Response to the United Nations Vote

In December of 1947 the White House received more than 100,000 letters and telegrams concerning Palestine.9 In the midst of the escalating and conflicting pressure, President Truman wrote to one of his assistants: “I surely wish God Almighty would give the Children of Israel an Isaiah, the Christians a St. Paul, and the Sons of Ishmael a peep at the Golden Rule.”10

On December 3rd the British announced they would terminate their League of Nations Mandate for Palestine on May 15, 1948. That same day the Arabs announced they would “defend their rights.”11

The British announcement and the hostile Arab response to it prompted a reconsideration of the American position in support of partition. The speed at which the process was moving seemed to spook the State and Defense Departments.

James Forrestal, the Secretary of Defense, together with the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reminded President Truman of the critical need for Saudi Arabian oil. The President responded by saying he would “handle the situation in light of justice, not oil.”12 Forrestal also told the President that in his opinion, “the Arabs would push the Jews into the sea.”13

The pressure from the State Department was even more intense because its career bureaucrats were all pro-Arab. They began to develop an alternative to the partition plan. Their idea was to replace the League of Nations Mandate with a United Nations Trusteeship.14 As the new year of 1948 arrived, extreme tension mounted between the White House and what President Truman called “the striped pants boys” at the State Department.15

The President’s contempt for the State Department did not apply to his Secretary of State, General George C. Marshall, even though Marshall was the strongest opponent to the establishment of the Jewish state. Truman greatly admired Marshall, and Marshall had the highest degree of public respect of anyone in the Truman Administration. The Secretary’s “Marshall Plan” for the reconstruction of Europe had caught the public imagination and had been hailed as a lifesaver throughout Europe. Marshall’s outstanding leadership resulted in his being selected as Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1947. Regarding Palestine, Marshall favored a “unitary state under a United Nations Trusteeship.”16

There were only two people in the Truman Administration who strongly supported the partition plan, and both of them were presidential advisers — David Niles and Clark Clifford. Clifford was Truman’s White House Counsel and confidant. Niles, who was Jewish, was one of only two Roosevelt aides who were retained by Truman when he became President. Niles was the President’s counselor regarding minority issues and patronage.

As a Jew, Niles had a natural sympathy for the terrible plight of the Jewish people who had survived the Holocaust. Clifford, on the other hand, based his support of Israel on his reading of ancient history and the Bible. He firmly believed the Jewish people were entitled to their homeland.17 Niles kept the key Zionist leaders informed of what was going on in Washington and within the White House. Clifford served to encourage the President to hold firm to his commitment to a Jewish state.

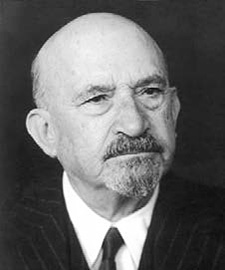

When the Zionist leaders learned of the strong opposition within the Truman Administration to the establishment of a Jewish state, they decided to send their foremost statesman and spokesman to Washington, D.C., to confer with the President. He was Chaim Weizmann (1874 – 1952).18

Two Crucial Jewish Voices

Dr Chaim Weizmann

Dr. Weizmann was a Russian Jew who had migrated to England where he had become a professor of chemistry. During World War I he greatly aided the British when he developed a synthetic form of acetone which was essential in the manufacture of cordite explosive. Some historians have suggested that this contribution to the British war effort is what prompted the Balfour Declaration. Weizmann served twice as president of the World Zionist Organization (1920-1931 and 1935-1946).

Despite his immense prestige, when Weizmann arrived in Washington, D.C., in March 1948, President Truman refused to see him. This was because the President had become irritated over all the Jewish pressure that was being applied to the White House, particularly by some American rabbis who had been very tactless. Besides, the President had already met with Dr. Weizmann the previous November, and during that meeting, the President had assured him of his support for a Jewish state.19

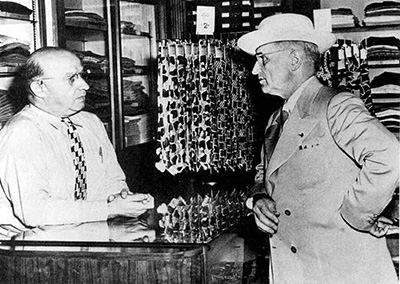

It was at this critical point in time that President Truman’s dear friend and former business partner, Eddie Jacobson, decided to intervene. The two had been partners in a clothing store business in Kansas City from 1919 to 1922. In his memoirs, Truman wrote that he never had a “truer friend.”20

Eddie Jacobson with Harry Truman

Jacobson was Jewish. He was not a Zionist, but he had a great compassion for the sufferings of the Jewish people. When he learned that Truman was refusing to see Weizmann, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge his old business partner to change his mind. Truman was impressed: “In all my years in Washington,” he wrote, “he had never asked me for anything for himself.”21

In response to Jacobson’s fervent personal plea, President Truman agreed to see Dr. Weizmann off-the-record on March 18th. They talked for almost an hour, and once again, the President assured Weizmann of his support for a Jewish state.22

In the third part of our study of the amazing events that led up to the prophesied rebirth of the nation of Israel, we’ll look at how the final decision played out in this historic event.

Notes

6. Sachar, pp. 284-285. See also O’Brien, p. 277.

7. Sachar, p. 292.

8. Ibid., p. 294.

9. David McCullough, Truman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), p. 598.

10. Harry S. Truman, Memoirs by Harry S. Truman: Years of Trial and Hope, Volume 2 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1956), p. 157.

11. Truman, p. 159.

12. McCullough, p. 597.

13. Ibid., p. 602.

14. Ibid., p. 601.

15. Ibid., p. 611.

16. Sachar, p. 290.

17. Bernard Weisberger, interview with Clark Clifford, American Heritage magazine, December 28, 1976.

18. The Jewish Visual Library, “Chaim Weizmann,” www.jewishvirtual library.org/jsource/biography/weizmann.html, accessed January 3, 2008.

19. Truman. pp. 157-158.

20. Ibid., p. 160.

21. Ibid.

22. McCullough, p. 608.